The Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) seeks to transform global gold production by integrating and formalizing the position of countless artisanal and small-scale miners. Executive director Lina Villa Córdoba talks to Jayne Flannery about ARM’s vision for the human face of the industry.

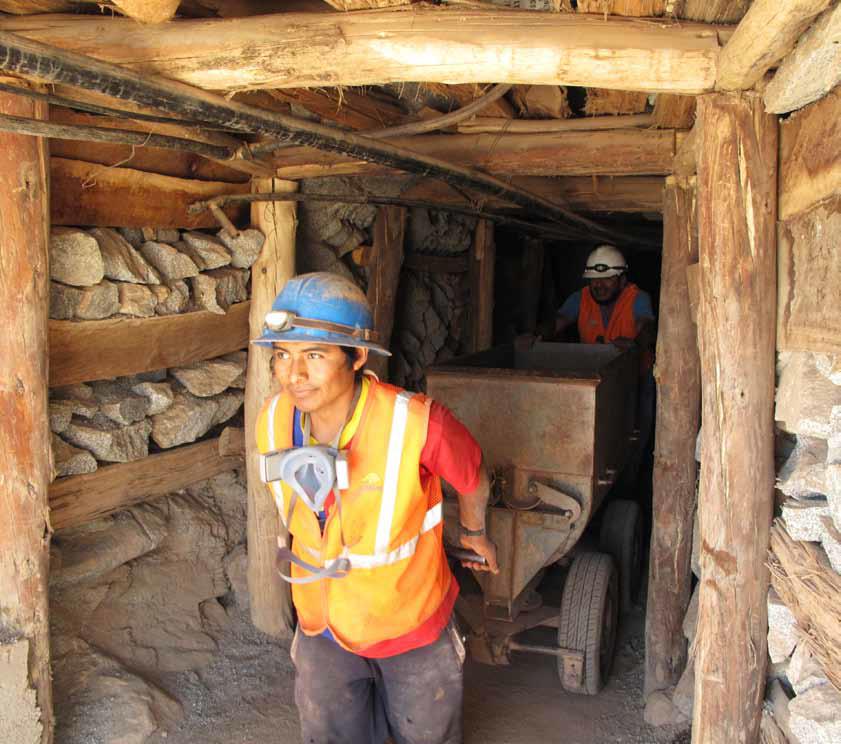

Measured by value and volume, the mining industry is dominated by a relatively small number of major industrial players, each typically holding a vast global asset portfolio. Yet at the base of the pyramid are innumerable indigenous artisanal and small-scale mining operators whose output may be measured in a couple of kilograms a day. The artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector continues to operate informally in development economies where this form of mineral extraction, relying on age-old technologies, has been of economic importance for generations.

Lina Villa Córdoba is executive director of The Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM), which is based in Colombia. Although the informal nature of ASM activity makes quantitative data capture a problem, information from local and international sources leads her to believe that approximately one hundred million people across South America, Africa and Asia are dependent on the ASM sector for their livelihoods. Around half of this population are reliant on gold mining.

“Large industrial producers account for about 90 percent of all the gold produced in the world, but the ASM sector constitutes 90 percent of the work force. It is the human face of the industry and any effort towards more socially responsible mining must take ASM into account,” she says.

The organization she represents is an independent, not-for-profit initiative with a global reach that campaigns for more just and equitable distribution of resources within the mining industry. ARM was established in 2004 to enhance equity and wellbeing in ASM communities through improved social, environmental and labor practices, good governance and the implementation of ecosystem restoration practices.

“ARM was born from the local initiative Oro Verde, or green gold,” she explains. “It centered on a group of organizations working together to support ASM miners in a bio-diversity hotspot where gold was the sought after mineral. Our remit was to upscale this work and take it to a global platform while continuing the focus on gold.”

Today, ARM is a networked organization that reaches out across all the main mining regions in the world.The original remit was to focus on South America, but ARM has more recently expanded its work into Africa and Asia where it has a particular focus on the ASM sector in Mongolia.

“We establish strategic alliances with national NGOs working on related issues and operate on the ground through national partners,” she continues. “Our contribution to the network is the development of tools and methodologies, advocacy at the global level and the development of standards for the ASM sector, such as the Fairtrade and Fairmined standard. We see ourselves as knowledge brokers in the network with particularly strong contacts in South America which we are working to replicate in other regions.”

ARM contends that improving the social and environmental performance of the ASM sector will positively impact on the lives of some of the world’s poorest people, while ignoring it can only aggravate conflict, poverty, inequity and environmental degradation.

Formalizing ASM

The strategy for realizing this vision is by pushing forward on multiple fronts to formalize the sector. Capacity building and meaningful negotiation and development are impossible when dealing with countless discrete operators. The development of formal entities capable of representing the sector’s interests in a fair and democratic way is a fundamental building block.

There are many aspects to formalization of the sector. Producers, for example, can obtain a better price for their output by being able to deal with more formalized intermediaries. Governments, in turn, are more likely to receive tax revenues to support development efforts. Formalization can also provide a focal point for work to improve the sector’s safety and environmental practices. It offers the potential to integrate producers’ co-operatives into national credit schemes – much needed if the sector is to gain access to improved, environmentally friendly technologies that eliminate the current reliance on mercury to amalgamate gold.

“Access to credit is vital to escape from the poverty trap in which most ASM miners currently exist, and if cleaner working practices are to be introduced. Meanwhile, it is completely unrealistic to have the same expectations of the ASM sector as of large industrial players who have huge resources at their disposal,” she says.

One of the most important benefits of formalization is the potential it offers to stabilize politically weak and volatile mineral rich regions by removing a funding route for arms. Throughout human history, mineral resources and conflict have gone hand in hand, and the trend continues. “History can show us a number of conflict situations which might have been fuelled by the ASM sector and in such areas there has to be a political will on the part of the state and the industry to ensure that ASM has developmental opportunities and is not contributing to a worsening of the situation.”

From another perspective, she points out that as the industry develops more and more voluntary standards, there is a growing collateral impact in terms of reputational risk to any buyer sourcing from the ASM sector. This inevitably damages local livelihoods and further limits market opportunities for the miners involved, creating a vicious downward spiral for those reliant on the sector.

Industrial engagement

ARM is now firmly established within the international development community and counts on support from a number of high profile donors. However, for Villa, the involvement and engagement of the major players in the industry is essential. “We have also established a producer’s support fund which has been created specifically to invite industrial players to join with us in working to strengthen the ASM sector,” she says.

“Larger companies operating in this industry are at the very center of the corporate social responsibility and sustainability debate,” she continues. “Today we see these companies increasing their collaboration and participation in a plethora of voluntary and mandatory sustainability initiatives which are being driven by advocacy organizations, national governments and the international community. These forces are converging to compel big players and transnational corporations to commit to a transformation of the sector. From our perspective at ARM, it is absolutely fundamental that the ASM sector should be part of this movement.”

Although some mining concessions are granted on previously “virgin” territory, it is frequently the case that the ASM sector is already active and may have been for many years. Activities that were previously informal can quickly be deemed illegal, often leading to violent conflict. Clashes between the two extremes of the industry have resulted in some mining operations having to be abandoned completely, and widespread criticism from human rights organizations. Such conflicts are ugly, costly and have involved industrial players in exactly the sort of publicity they seek at all costs to avoid, leading in some instances to the withdrawal of institutional investors and government support.

“More and more large companies are recognizing that it is in their interests to support and formalize the ASM sector, as that is the only way to open a formal path for negotiation,” says Villa. “The conflicts we see with the ASM sector will not go away on their own and formalization is the only way for state actors and industrial players to engage in a positive dialogue with the sector.

“The mining industry has a particularly important role to play because of its strong leverage position with national governments. It can also contribute by formalizing informal agreements that grant concessions to the ASM sector. The miner then has a legal right to use the resource and his obligations and relationships are transformed in a way that can benefit everyone. There is a real opportunity for industrial players to address the potential for social and economic development that ASM offers and push for positive transformation in the sector.”

Villa is not an advocate of mandatory legal enforcement of corporate social responsibility, but believes in working through a process of consensus and knowledge-sharing with the industry’s larger players. “When CSR is linked to binding obligations, its scope for achieving true sustainability becomes limited and it is reduced to a tick box exercise. All corporations must take note of markets and consumers, though, and we see these as key agents of change and the main driver of the steps forward we have witnessed to date.”

However, Villa does want to see the value creation opportunities inherent in mining distributed more equitably throughout the entire supply chain. To date, the impetus for greater social and environmental responsibility has focused primarily on initiatives led by the industrial-scale mining and jewelry industries. Although these steps towards improving performance and transparency are critical, she points out that they exclude millions of ASM producers and so limit the social and economic development opportunities of the industry.

ARM is setting new standards for responsible ASM production to enable producers to deliver metals and minerals through "fairly mined" supply chains to the market. The organization believes ASM can become a socially and environmentally responsible activity and contribute more fully to improving the life chances of marginalized artisanal miners, their families and communities.

The biggest environmental challenge associated with the ASM sector is the continuing use of mercury as an amalgamation agent in the extraction process. It represents a dangerous hazard for anyone in contact with it and is a major environmental contaminant. Villa is keen to point out that the low level of development within the ASM sector means it cannot be expected to conform to the same standards as established mining companies.

Meanwhile ARM is a keen supporter ofthe UNEP Global Mercury Partnership which is committed to changing working practices in the ASM sector. “It is important that the use of mercury is not simply banned,” she comments. “If we took this step, it would just lead to the emergence of a new black market with even fewer controls than we have today. Artisanal and small scale miners do not like using mercury, but they do not have access to the knowledge and resources to support viable alternatives.

“ARM promotes mercury-free artisanal mining as the best available technology, but at the same time we acknowledge that mercury plays a central role in the current ASM approach to processing. Any move to reduce and eliminate its use must be accompanied by capacity building and technical support for the miners involved.”

With their in-depth knowledge of mining processes, safety, productivity and efficiency optimization and access to advanced green technologies, established mining companies could be invaluable partners in promoting new and improved working practices for their small-scale counterparts. Such initiatives could form the basis for CSR initiatives that could transform communities at very little cost, dramatically improve community relations and greatly enhance the security of state-granted concessions.

Looking to the future, Villa hopes to see the mining industry as a whole evolving towards harmonization of the assorted array of voluntary standards that have been adopted to date and are still under development. “The next step forward is a global institutionalized mechanism to ensure harmonization of all the different standards that exist. My vision for the future of this industry is a holistic one where the mining industry exists as a single industry and all actors and stakeholders have an equitable say in its development”.

“For formalization to make sense there must be a business case. The potential benefits must make sense to the industry, to governments and of course to the miners themselves. Without the involvement of all these different actors and stakeholders, it will be very difficult to create an environment for this sector to improve,” she concludes.

www.communitymining.org. http://www.facebook.com/communitymining

Twitter: @communitymining

DOWNLOAD

ARM-AM-May12-Bro-s.pdf

ARM-AM-May12-Bro-s.pdf